Find out more about the historic first test, which could be used to defend our planet if a hazardous asteroid were discovered. Plus, explore lessons to bring the science and engineering of the mission into the classroom.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Update: Oct. 4, 2022 – The DART spacecraft successfully impacted the asteroid Dimorphos on September 26. See the latest news and images on the mission website.

In an attempt to alter the orbit of an asteroid for the first time in history, NASA will crash a spacecraft into the asteroid Dimorphos on September 26. The mission, known as the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, will take place at an asteroid that poses no threat to our planet. Rather, it’s an ideal target for NASA to test an important element of its planetary defense plan.

Read further to learn about DART, how it will work, and how the science and engineering behind the mission can be used to teach a variety of STEM topics.

Why It’s Important

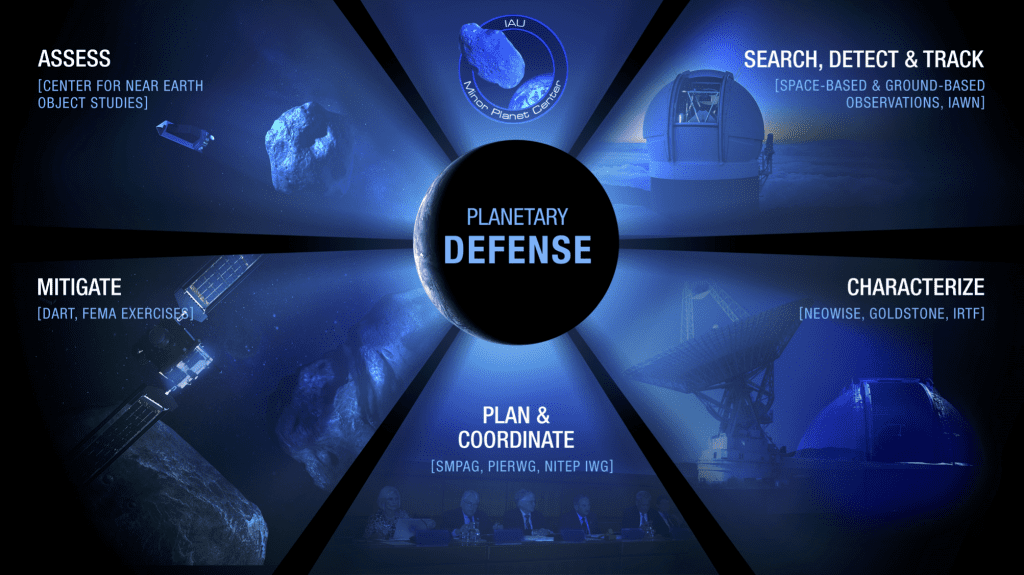

The vast majority of asteroids and comets are not dangerous, and never will be. Asteroids and comets are considered potentially hazardous objects, or PHOs, if they are 100-165 feet (30-50 meters) in diameter or larger and their orbit around the Sun comes within five million miles (eight million kilometers) of Earth’s orbit. NASA’s planetary defense strategy involves detecting and tracking these objects using telescopes on the ground and in space. In fact, NASA’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies, or CNEOS, monitors all known near-Earth objects to assess any impact risk they may pose. Any relatively close approach is reported on the Asteroid Watch dashboard.

While there are no known objects currently posing a threat to Earth, scientists continue scanning the skies for unknown asteroids. NASA is actively researching and planning for ways to prevent or reduce the effects of a potential impact, should one be discovered. The DART mission is the first test of such a plan – in this case, whether it’s possible to divert an asteroid from its predicted course by slamming into it with a spacecraft.

With the knowledge gained from this demonstration, similar techniques could be used to deflect an asteroid or comet away from Earth if it were deemed hazardous to the planet.

How It Works

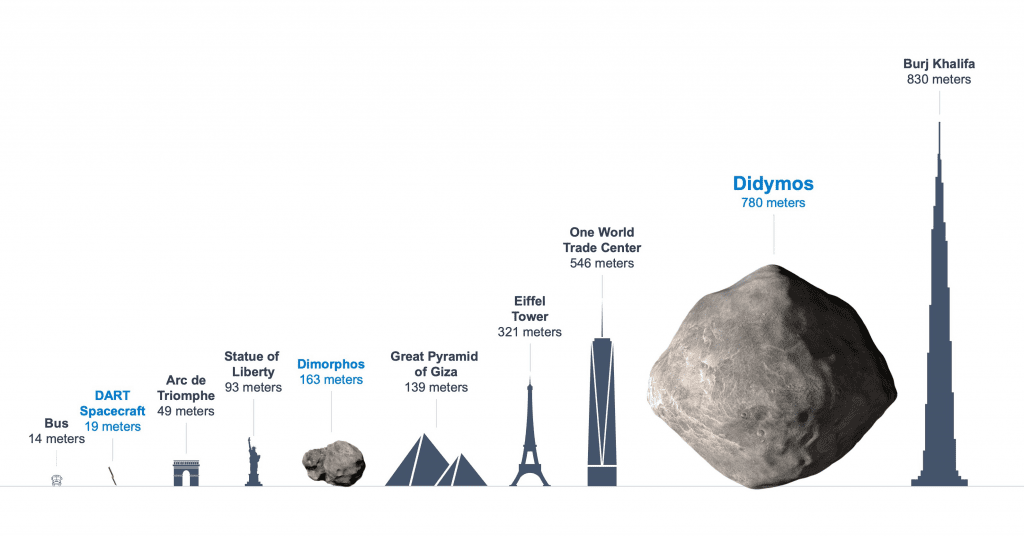

With a diameter of about 525 feet (160 meters) – the length of 1.5 football fields – Dimorphos is the smaller of two asteroids in a double-asteroid system. Dimorphos orbits the larger asteroid called Didymos (Greek for “twin”), every 11 hours and 55 minutes.

Neither asteroid poses a threat to our planet, which is one reason why this asteroid system is the ideal place to test asteroid redirection techniques. At the time of DART’s impact, the asteroid pair will be 6.8 million miles (11 million kilometers) away from Earth as they travel on their orbit around the Sun. Regardless of how much or how little the orbit of Dimorphos is changed by DART, the asteroid will not become a threat to Earth.

The DART spacecraft is designed to collide head-on with Dimorphos to alter its orbit, shortening the time it takes the small asteroid to travel around Didymos. Compared with Dimorphos, which has a mass of about 11 billion pounds (five billion kilograms), the DART spacecraft is light. It will weigh just 1,210 pounds (550 kilograms) at the time of impact. So how can such a light spacecraft affect the orbit of a relatively massive asteroid?

You can use your mouse to explore this interactive view of DART’s impact with Dimorphos from NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech | Explore the full interactive

DART is what’s known as a kinetic impactor because it will transfer its momentum and kinetic energy to Dimorphos upon impact, altering the asteroid’s orbit in return. Scientists can make predictions about some of these effects thanks to principles described in Newton’s laws of motion.

Newton’s first law tells us that the asteroid’s orbit will remain unchanged until something acts upon it. Using the formula for linear momentum (p = m * v), we can calculate that the spacecraft, which at the time of impact will be traveling at 3.8 miles (6.1 kilometers) per second, will have about 0.5% of the asteroid’s momentum. The momentum of the spacecraft may seem small in comparison, but it’s enough to make a detectable change in the speed of Dimorphos’ orbit.

But there is more to consider in testing whether the technique could be used in the future for planetary defense. For example, the formula for kinetic energy (KE = 0.5 * m * v2) tells us that a fast moving spacecraft possesses a lot of energy.

When DART hits the surface of the asteroid, its kinetic energy will be 10 billion joules! A crater will be formed and material known as ejecta will be blasted out as a result of the impact. In this case, asteroid material equalling 10-100 times the mass of the spacecraft itself will be ejected out of the crater. The force needed to push this material out will be matched by an equal reaction force pushing on the asteroid in the opposite direction, as described by Newton’s third law.

How much material will be ejected, and its recoil momentum, is still unknown. A lot depends on the surface composition of the asteroid. Laboratory tests on Earth suggest that if the surface material is poorly conglomerated, or loosely formed, more material will be blasted out. A surface that is well conglomerated, or densely compacted, will eject less material. As a result, the impact will also tell us more about the composition of Dimorphos.

After the DART impact, scientists will use a technique called the transit method to see how much the impact changed Dimorphous’ orbit. As observed from Earth, the Didymos pair is what’s known as an eclipsing binary, meaning Dimorphos passes in front of and behind Didymos from our view, creating what appears from Earth to be a subtle dip in the combined brightness of the pair. Scientists can use ground-based telescopes to measure this change in brightness and calculate how quickly Dimorphos orbits Didymos.

One of the biggest challenges of the DART mission is navigating a small spacecraft to a head-on collision with a small asteroid millions of miles away. To solve that problem, the spacecraft is equipped with a single instrument, the DRACO camera, which works together with an autonomous navigation system called SMART Nav to guide the spacecraft without direct control from engineers on Earth. About four hours before impact, images captured by the camera will be sent to the spacecraft’s navigation system, allowing it to identify which of the two asteroids is Dimorphos and independently navigate to the target.

DART is not just an experimental asteroid impactor. The mission is also using cutting-edge technology never before flown on a planetary spacecraft and testing new technologies designed to improve how we power and communicate with spacecraft.

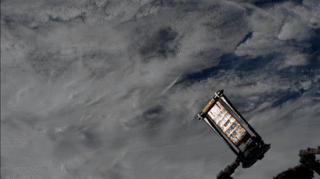

One such technology that was first tested on the International Space Station and is being used on the solar-powered DART spacecraft, is the Roll Out Solar Array, or ROSA, power system. As its name suggests, the power system consists of flexible solar panel material that is rolled up for launch and unrolled in space.

Some of the power generated by the solar array is used for another innovative technology, the spacecraft’s NEXT-C ion propulsion system. Rather than using traditional chemical propulsion, DART is propelled by charged particles of xenon pushed from its engine. Ion propulsion has been used on other missions to asteroids and comets including Dawn and Deep Space 1, but NEXT-C’s ion thrusters have higher performance and efficiency.

Follow Along

There are a number of ways to follow along with this exciting event and all the science from the mission.

On September 26, watch NASA Live from 3 to 4:30 p.m. PDT (6 to 7:30 p.m. EDT) to hear commentary from experts before and during the impact at Dimorphos. Images from DART, which will impact the asteroid at 4:14 p.m. PDT (7:14 p.m. EDT), will be streamed to Earth in real-time and shown during the broadcast.

In the days following the event, NASA expects to receive images of the impact from a cubesat that will be deployed by DART before impact. The cubesat, LICIACube, which was provided by the Italian Space Agency, is designed to capture images of the impact, the ejecta cloud, and perhaps even the impact crater left behind by DART. The James Webb Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the Lucy spacecraft will observe Didymos to monitor how soon reflected sunlight from the ejecta plume can be seen. In the following weeks, DART team members will continue observing the asteroid system to measure the change in Dimorphos’ orbit and determine what happened on its surface. In 2024, the European Space Agency plans to launch the Hera spacecraft to conduct an in-depth post-impact study of the Didymos system.

Learn more about DART and see the latest images and updates on the mission website. Plus, explore even more resources on this handy page.

Teach It

The mission is a great opportunity to engage students in the real world applications of STEM topics. Students can even observe the results of their engineering design challenges at the same time as the results of the mission are streamed back to Earth! Start exploring these lessons and resources to get students engaging in STEM along with the mission.