New immigrant arrivals to the United States face many challenges and obstacles when navigating their daily lives. For Asian immigrants, these include language and cultural obstacles that impact those who arrive with little to no proficiency in English. But navigating life in America also impacts English-speaking immigrants as they adjust to life in a new country with its own unique linguistic and cultural quirks.

A little over half of Asian Americans (54%) were born outside the United States, including about seven-in-ten Asian American adults (68%). While many Asian immigrants arrived in the United States in recent years, a majority arrived in the U.S. over 10 years ago. The story of Asian immigration to the U.S. is over a century old, and today’s Asian immigrants arrived in the country at different times and through different pathways. They also trace their roots, culture and language to more than 20 countries in Asia, including the Indian subcontinent.

In 2021, Pew Research Center conducted 49 focus groups with Asian immigrants to understand the challenges they faced, if any, after arriving in the country. The focus groups consisted of 18 distinct Asian origins and were conducted in 17 Asian languages. (For more, see the methodology.)

Across the focus groups, daily challenges related to speaking English emerged as a common theme. These include experiences getting medical care, accessing government services, learning in school and finding employment along with speaking English and understanding U.S. culture. Participants also shared frustration, stress and at times sadness because of the cultural and language barriers they encountered. Some participants also told us about their challenges learning English, as well as the times they received support from others to deal with or overcome these language barriers.

Among Asian immigrants, recent arrivals report lower English proficiency levels than long-term residents

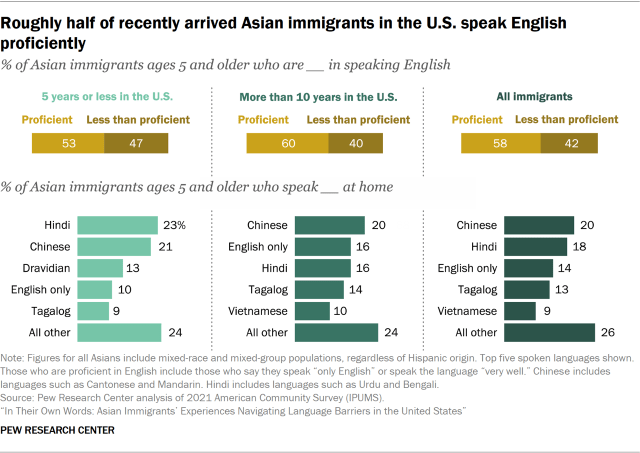

Focus group findings about learning English and challenges navigating life in the U.S. are reflected in government data about English proficiency among Asian immigrants. For example, about half (53%) of Asian immigrants ages 5 and older who have been in the U.S. for five years or less say they speak English proficiently, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data. By contrast, 60% of Asian immigrants who have been in the U.S. for more than a decade say they speak English proficiently, a higher share than recent arrivals.

Among Asian Americans ages 5 and older, 58% of immigrants speak English proficiently, compared with nearly all of the U.S. born who say the same (94%).

There is language diversity among Asian immigrants living in the U.S. The vast majority (86%) of Asian immigrants 5 and older say they speak a language other than English at home, while 14% say they speak only English in their homes. The most spoken non-English language among Asian immigrants is Chinese, including Mandarin and Cantonese (20%). Hindi (18%) is the second most commonly spoken non-English language among Asian immigrants (this figure includes Urdu, Bengali and other Indo-Iranian and Indo-European languages), followed by Tagalog and other Filipino languages (13%) and Vietnamese (9%). This reflects the languages of the four largest Asian origin groups (Chinese, Indian, Filipino and Vietnamese) living in the U.S. But overall, many other languages are spoken at home by Asian immigrants.

The following chapters explore three broad themes from the focus group discussions: the challenges Asian immigrants have faced in navigating daily life and communicating in English; tools and strategies they used to learn the language; and types of help they received from others in adapting to English-speaking settings. The experiences discussed may not resonate with all Asian U.S. immigrants, but the study sought to capture a wide range of views by including participants of different languages, immigration or refugee experiences, educational backgrounds and income levels.

Where Asian immigrants face language challenges: Navigating daily life and communicating in English

Many focus group participants described how difficulties speaking English impacted their ability to carry out daily tasks like shopping, going to the doctor or visiting a government office, highlighting the many ways in which not being able to communicate can make daily life challenging. For example, simple activities such as visiting stores or purchasing food were difficult to complete.

“I came here when I was in college. I couldn’t speak English at all … I couldn’t speak in English at the post office or the grocery store.”1

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-30s

“I didn’t know a single word [of English] when I first came here. … The language is very different. I didn’t know how to order food when dining out.”

–Immigrant woman of Vietnamese origin in early 40s

Some participants mentioned that when they struggled to speak in English, they noticed frustration from people they were interacting with. A Taiwanese woman described her experience at stores:

“Because my English isn’t that good, I often feel slighted by shopkeepers … some lose their patience with me.”

–Immigrant woman of Taiwanese origin in late 30s

Using public transportation also presents barriers. A Burmese woman recalled her initial challenges with a local bus system due to not being able to ask for help in English:

“I didn’t know where the bus stops were. I didn’t know how to ask so I walked … I couldn’t speak the language.”

–Immigrant woman of Burmese origin in early 50s

Visiting medical offices was highlighted as another place where newly arrived immigrants faced challenges, including not being able to accurately describe ailments.

“There are a lot of obstacles … we can’t communicate … it is difficult … particularly [when] going to see a doctor. Sometimes we want to talk about our conditions or our health conditions, but we don’t know the words in English, especially my parents … sometimes, I have to go with them and don’t know how to explain things to the doctor.”

–Immigrant woman of Cambodian origin in mid-20s

Another Cambodian woman shared her language challenges while visiting the doctors during her pregnancy:

“I had hardships once I arrived in the [United States]. Yes, it was very difficult. … I didn’t know the [English] language yet … especially [when] I was pregnant. … Every time I went to see doctors … there were no interpreters. So it was difficult to talk to them.”

–Immigrant woman of Cambodian origin in mid-40s

Meanwhile, some participants had difficulties with English during their visits to government offices, including while filling out paperwork.

“When I just came here and had to go to government offices for various procedures, it was easier to understand if there was a Japanese person who could explain in Japanese, but if they explained in English, I didn’t understand English and had absolutely no idea what I was supposed to do.”

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-40s

“When I go to places like the DMV and other place to do some paperwork, I have a hard time when the documents are all in English.”

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-30s

English proficiency challenges at school and college

Many participants mentioned their educational experiences in the U.S. and the communication obstacles they faced. For some, this happened when they were school-age children or teenagers, newly arrived in the U.S. For others it happened when they arrived in the country to begin their university studies.

Other participants shared that they had learned English in their places of origin prior to arriving in the U.S. Yet, they found themselves facing challenges as they transitioned into predominantly English-speaking environments. Some attribute these challenges to their lack of fluency and comfort in English despite understanding what others were saying to them. Some participants also indicated that their accents led to confusion when communicating with English speakers.

“When I first arrived, I was only 10 years old, and with poor English language skills. Then, I found myself in a class full of other Chinese students. It was difficult to learn English that way as everybody could speak Chinese, so you would not talk to them in English. [My] progress was very slow.”

–Immigrant woman of Chinese origin in early 30s

There were participants who recalled feelings of fear at school, not only because they did not know the language but because they did not understand how American society and schools functioned. One immigrant woman of Vietnamese origin recalled not knowing whom to ask for help because no one in her family understood American culture.

“When I came to the U.S. … I went to high school immediately … my parents went to work to earn money, so I had to go to school. … But at that time, I felt very scared. I didn’t understand what people talked [about] in school at all. It was not only English, but also culture and other things, everything was different in school. Coming home, I didn’t know who to ask; no one in my family knew. Because my family came here under the sponsorship. … There were many things I didn’t understand about the culture here. I didn’t know; I didn’t dare to ask.”

–Immigrant woman of Vietnamese origin in early 40s

A portion of focus groups participants came to the United States in their teenage years. These participants recalled challenging situations at school regarding their English skills. Some participants knew no English and reported having to take hours of English as a second language (ESL) classes, which left them behind in other classes in high school.

“I was already old when I first came because I was 14. I attended ninth grade but failed. I moved down to seventh grade because I could not do it. In seventh and eighth grade, it was challenging because I could not keep up with others in any of the classes in high school. I moved to ESL to learn the English language. I attended two, three hours and then I joined others again. It was a waste.”

–Immigrant woman of Laotian origin in early 50s

Several participants immigrated to the United States to study at a college or university and reported challenges speaking English and navigating U.S. culture. This included feeling insecure in their language abilities as well as other students not being able to understand them.

“As a university student, the language barrier was a problem for me. Even though I started out from a language school and acquired a certain level of English, I was still embarrassed to speak English at the university, could not participate in discussions at all, and I was also embarrassed and frustrated when I had to speak. I knew my classmates stared at me like ‘I can’t understand what she’s saying at all.’ It felt really tough to attend classes. It’s also about the language barrier and it was a struggle at first.”

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-30s

Several top schools in the United States require the Test of English as a Foreign Language, or TOEFL, to determine the language abilities of non-native English-speaking applicants. Some participants reported that despite passing this test and obtaining a top score, they experienced challenges keeping up in college-level courses in the U.S. Even in non-academic social settings, some recalled not fully understanding what native English speakers were saying due to their use of slang and frequent pop culture references.

“I remember when I began my university, almost 50% of the classes were incomprehensible. You thought you had already got a very good TOEFL score, right? I took a score above 100 or 110, and it was the ceiling, and it turned out that you really didn’t understand the instruction. When I was in college, I remember many times when I made friends, they might be the native English speaker. When I couldn’t understand, I quietly remembered that word and then went back to look it up in the dictionary. … People often say it, but it is not used in academics. Later, I found that my English improved a bit. When you really interact more with local people, you will slowly get used to the pop culture and those words. Then you need to have something appealing when you communicate, you further your learning by watching more American TV shows.”

–Immigrant woman of Chinese origin in late 20s

“At first, I came here to study for a master’s degree as an international student, but I couldn’t speak a single word of English when I first met the head of the department. I only took the TOEFL and GRE tests. The head of the department said, ‘You don’t seem to be ready for classes. Then take only one class and register for the language training.’ So I started taking language training for six months and moved my school to another place.”

–Immigrant man of Korean origin in early 40s

English proficiency and the workplace

Many participants pointed to their difficulties speaking in English as a major reason they struggled to find employment. One Taiwanese man mentioned:

“I wanted a job all along, but there were obstacles. I started sending out my resume … but it wasn’t successful. I think it was mainly due to my poor communication skills. There were usually four stages in an interview, starting with a phone interview. I never got to stage four, as I usually would fail at stage one.”

–Immigrant man of Taiwanese origin in early 40s

A Taiwanese women described the challenges of finding a job:

“The hardest thing was to find a job. Due to poor language ability, I could not express myself well during interviews, and this was the biggest challenge.”

–Immigrant woman of Taiwanese origin in late 40s

Some participants shared that once employed, language barriers slowed their professional success and advancement. A Chinese woman described how language challenges emerged when she changed industries.

“I just changed jobs, and this job was very different from what I did before, so the terminology used at work now is completely different from the previous work environment. It is like relearning the language of a new field, that is, I do not have the breadth that the native English speakers have, because I did not get exposed to all the words they use.”

–Immigrant woman of Chinese origin in early 30s

A Japanese woman shared her belief that her lack of proficiency speaking English negatively affected her ability to get customers as a hairdresser.

“I had been working as a hairdresser in Japan for quite a long time, so I thought I could do well in the U.S. as well, but the language barrier made it difficult to get customers … for the first year.”

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-40s

Some participants noted their accents affected how they were treated at work.

“When starting to work … many times on the phone, I had to make phone calls to customers, then they heard my accent; they were obviously talking to my co-workers in different ways than they talked with me. Their attitude was totally different.”

–Immigrant woman of Vietnamese origin in early 40s

“I was working as an office administrator. Actually, I was also an operator, but since I have an accent with my English, then I wasn’t allowed to pick up the phone. Because they don’t want the company’s credibility to go down.”

–Immigrant woman of Indonesian origin in late 30s

BY LUIS NOE-BUSTAMANTE, LAUREN MORA AND NEIL G. RUIZ